Hadassa Noorda

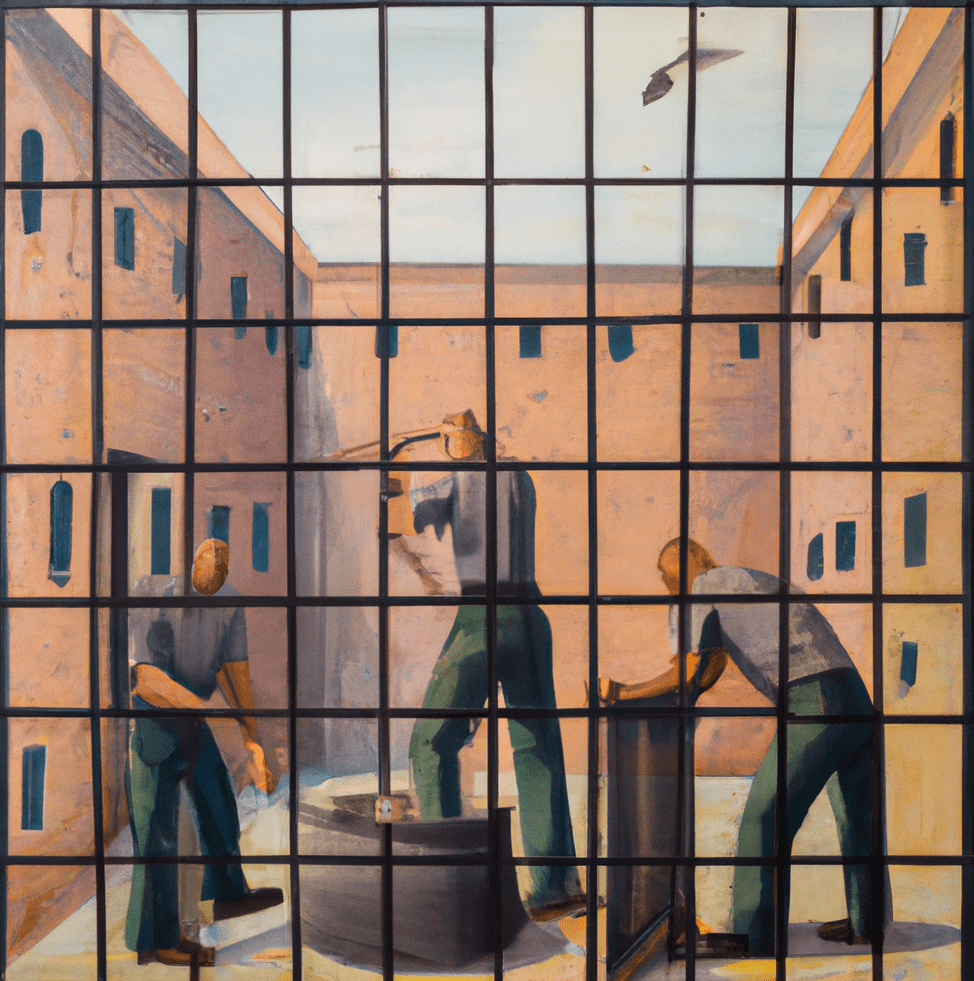

The Netherlands recently shifted to a voluntary work scheme for prisoners. This might be viewed as a better alternative to compulsory prison labor. Having work opportunities while in prison is said to contribute to the learning of skills, promote rehabilitation and societal reintegration, and provide prisoners with income (for analyses of the positive aspects of prison labor, see Smith, Mueller and Labrecque; Sampson and Laub; Kuppens, van Esseveldt, van Wijk; Report by the Howard League for Penal Reform). However, prison labor raises several concerns regarding the position of captive workers. Those doing work in prison are in vulnerable and disadvantaged positions because they often perform their work for low pay in conditions of subordination, with limited freedom of movement, the inability to change jobs, and limited labor and social security rights (see Mantouvalou here and Lippke here). In addition, they have limited privacy because they are under constant surveillance. Further problems include the quality of work and the limited number of work opportunities.

In this blog post, I argue that although work in Dutch prisons is to some extent voluntary, the legal status of captive workers is far removed from that of regular employees, as they work for low pay and have no right to meaningful work options. This raises profound questions about their rehabilitation. I explore these issues based on the principle that prisoners ought to retain their basic rights, except for the loss of liberty, and propose amending the approach to prison labor in the Netherlands. This blog post aims to provide useful context for the analysis of prison labor in general.

Is work in Dutch prisons voluntary?

For prisoners in the Netherlands, there is no direct obligation to work, which means that the state does not use physical force or deny basic necessities to compel prisoners to work. Yet, work in prison is considered to be a means of stimulating prisoners’ desirable behaviors, and a positive evaluation of prisoners’ work is an important aspect in granting them particular privileges, such as less repetitive and more challenging work options, more possibilities for visits from family and friends, and more time for education. The privilege of work can be taken away when prisoners do not behave according to a certain norm, leaving prisoners in their cells for most of the day (Boone, p. 231–249). Whether they behave according to this norm is determined by prison staff, who report on their behaviors and conduct risk analyses. This regime is said to contribute to prisoners’ motivation to work and reintegrate into society. This means that prisoners are considerably less free to decide whether to work than laborers who are not in prison.

In present-day Dutch prisons, inmates generally work 20 hours a week, which is said to be the minimum needed for resocialization and is supposed to contribute to the reduction of recidivism. Although the Dutch government is striving for the normalization of working hours in prison, wages are not part of the normalization effort. Prisoners generally work for 95 euro cents per hour. Employed by In-Made, a production company established by the Dutch Judicial Institutions Service that regulates prison work in the Netherlands, prisoners mainly perform production work, such as packing and assembling as well as cleaning and laundry jobs, in the facility. Opportunities for engagement in more specialist work and taking courses and gaining certificates is subject to demonstrable good behavior. In addition, prisoners may work outside the facility during the final phase of their sentences if they demonstrate good behavior.

“Offenders are sent to prison as punishment, not for punishment.”

Why is it important to facilitate people’s reintegration upon release from prison? The instrumentalist approach to addressing this question is based on the claim that offenders’ reintegration reduces recidivism and increases public safety. As Lippke puts it, “many who support prison labour do so precisely because they believe that it helps inmates avoid the destructive effects of prison idleness and acquire the job skills, work experience, and work habits the absence of which contributed to their delinquency in the first place.” This is in line with the aim of the Dutch prison scheme to contribute to the reduction of recidivism.

However, this argument can be countered with empirical facts. Mantouvalou argues that instead of promoting prisoners’ reintegration, rules on prison labor “increase the vulnerability of incarcerated people and are connected to structures of exploitation.” Prisoners often do not gain any useful skills that will benefit their future employability and reintegration and, on top of that, private businesses benefit from prisoners’ labor, as prisoners often perform jobs for which companies have difficulties recruiting employees, and their labor costs are lower (Mantouvalou, Structures of Injustice and Workers’ Rights, OUP, 2023, p. 17; see also this article by Pandeli, Marinetto, Jenkins, p. 604).

A more fruitful way of addressing the question of why reintegration should be facilitated is based on the principle that prisoners ought to retain their basic rights (for an analysis of this principle, see this article by Van Zyl Smith. For critical analyses of intrusive forms of rehabilitation, see, e.g. this article by Forsberg and Douglas, this article by Duff and this article by Meijer). Imprisonment is a source of various harmful effects for inmates and their relatives. The idea is that these effects ought to be counteracted not only with an eye on reducing recidivism and increasing public safety but also on the ground that “offenders are sent to prison as punishment, not for punishment.” (This well-known line is from early 20th-century prison commissioner Alexander Paterson. Quoted in this article by Van Zyl Smith). This means that prison should not be punitive in any other way than through the loss of liberty (Van Zyl Smith, p. 31–32). Against this background, Rotman develops a notion of rehabilitation that counteracts the harmful aspects of imprisonment (see Rotman here). According to Rotman, rehabilitation functions as a counteractive force to imprisonment, creating duties on the part of the state to reduce the negative effects of imprisonment and to reintegrate offenders upon release. This notion captures a concern that runs more deeply than simply empirical data about recidivism: for Rotman, offenders ought to retain their basic rights.

In what follows, I am primarily interested in the impact of imprisonment on the employment of released offenders.

Illegitimate extension of the prison sentence in society

Imprisonment significantly affects the employability of those who have served a prison sentence. As studies show, work in prison, although beneficial at first sight, does not mitigate this negative effect on life after imprisonment. Those with a criminal history are excluded from many work opportunities, particularly jobs that are not precarious, and face obstacles when attempting to find better work (see Augustine here). Often, prejudice rather than unsuitability is the underlying reason for this exclusion. It may be argued that as in many other jurisdictions, disclosing criminal records is not always required in the Netherlands; however, it has been observed that those who have been in prison “come to expect—and sometimes embrace—low-wage precarious work outside prison” (for an analysis, see Mantouvalou, p. 15). In addition, people in prison often experience stress, and the closed characteristics of prisons have depersonalizing effects on them (Goffman). This may impact their employability upon release. One person in prison describes the following:

You have to be able to get through a job interview after a more or less long prison sentence. It means to be able to forget the time spent inside in order to show self-confidence in body language and speech. It means being able to speak on free and equal terms; it also means being able to “sell” oneself after time spent being a nobody (French inmate quoted in this article by Shea, p. 136).

Prisoners’ bleak expectations about the job market have been confirmed by various empirical studies. For example, it was found that in the first year following their release, only 25% of prisoners in Austria and Britain found a stable, full-time job (Shea, p. 134).

Returning to society as a productive member is, however, important for most people. Work is “a, if not the, primary source of identity, status, and access to other goods in most modern societies.” It provides people with income that they can use to support themselves and their dependents, and it influences the quality of their lives to an important extent. Work also plays an important role in determining how people are perceived by others and by themselves, and it gives people’s lives structure. Because of the value and benefits of work, access to work is a crucial aspect to living a normal life.

The impact of imprisonment on the employability of formerly imprisoned people after release can be such that they cannot live a normal life. Their sentences are, in fact, extended outside the walls of the actual prison. The concept of exprisonment, which describes practices of restraint that do not subject individuals to prison or jail sentences but do deprive them of liberty, is a useful tool for understanding these negative impacts (this concept was first introduced in this article by Noorda). Other practices that have been viewed through this lens include electronic monitoring and travel bans. Many of the negative effects of imprisonment are shared by these exprisoning measures (see also this blog post by Mantouvalou and Noorda). In most cases, such measures do not exclude individuals from living their lives altogether, and they are not intended as punishment; however, their effects can be as severe as traditional imprisonment, especially when several measures are applied to one person (see this article by Noorda, p. 6). Exprisonment may also spill over into the lives of relatives, similar to how imprisonment can cause hardships to third parties (see e.g. this article by Von Hirsch, p. 162). Not having access to paid labor upon release or having their employability affected by their prison sentences may also potentially result in (partial) exprisonment, as formerly imprisoned people have only limited access to this crucial aspect of living a normal life.

Implications

In this blog post, I have sought to argue that as formerly imprisoned people experience major obstacles participating in the labor market, prison sentences are illegitimately extended outside the walls of the actual prison. The current work scheme for prisoners in the Netherlands is not organized to counteract these negative impacts of imprisonment. Although, work in Dutch prisons is meant to serve reintegration purposes, these are pursued to increase public safety by reducing recidivism, while rehabilitation is important not only for instrumentalist reasons but also because prisoners ought to retain their basic rights.

Based on the principle that with the exception of a temporary loss of liberty, prisoners ought to retain their basic rights, I propose an obligation whereby states should counter the extension of prison sentences outside the walls of the actual prison in two ways: First, I suggest that to counteract the negative impacts of imprisonment, states should facilitate meaningful work options for all prisoners. Under the current Dutch scheme, prisoners are allowed to work when they comply with a certain desired norm of showing good behavior, but they do not have the right to work. In addition, a positive evaluation of their labor is an important aspect in deciding whether prisoners are allowed the privilege of more challenging work options. Meaningful access to the labor market and living a normal life upon release can be difficult for prisoners because of, among other negative impacts, a lack of education, skills, and experience. Providing all prisoners with the right to meaningful work opportunities will help prisoners gain the requirements needed to participate in the job market upon release.

Second, states should counteract the negative impacts of imprisonment by applying a minimum wage requirement for work in prison. Prison labor should provide prisoners with an adequate income to support their dependents, pay their debts, and leave prison with enough money to effectively reintegrate into society. The low level of pay under the current work scheme in Dutch prisons does little for prisoners’ rehabilitation. Those in prison can buy basic consumer goods in the facility, but they can neither support their dependents nor pay their debts. The application of a minimum wage requirement for work in prison would contribute to prisoners’ societal reintegration upon release and counter the negative effects of imprisonment, both during imprisonment and upon release. Some may argue that offenders have forfeited all or some of their rights, including the right to reintegrate into society after having served their sentences (for related arguments regarding the forfeiture of rights in prison, see e.g. Morris; Goldman). The Dutch prison scheme seems to be based on this argument, as it portrays work in prison as a privilege instead of a right. However, this goes against the principles that imprisonment ought not to be extended beyond the prison term itself and that prisoners retain their basic rights. Instead, I have sought to argue that states ought to counteract the negative effects of prison sentences. Meaningful work options and a minimum wage for prisoners would not only contribute to prisoners’ reintegration but also help in countering the illegitimate extension of their prison sentences into society.